|

By Ryan Tibbens

Before proceeding, please read this article from the Chronicle of Higher Education in which they detail JMU’s X-Labs class, a new project-based, experience-based, experimental design in which students work collaboratively and creatively. At least read the first half. Okay, fine, here’s the essential concept for you bums: "Tackling big problems is the point of JMU X-Labs, a four-year-old experiment in undergraduate education. Through a blend of interdisciplinary collaboration, project-based learning, and unscripted, open-ended research, each course takes students through the long and often aggravating process of developing new ways of thinking about complex problems. They might design drones to help with environmental problems, tackle foreign-policy challenges, build autonomous vehicles, or develop medical innovations to help with the opioid crisis. If everything goes well, students will produce a prototype of a product, plan, or service in 15 weeks." [Link]

If that sounds interesting, check out the article and JMU X-Labs’ website. If that sounds ridiculous, it might be even more important for you to check out the article because the education pendulum is swinging fast, and project-based and/or interdisciplinary learning (hopefully) is coming next. Whether you want to ride or dodge the pendulum, you should know more about interdisciplinary learning than your school’s mandatory training is providing, including what is happening at the college level.

I find myself in an interesting position because of my age and role as former student and current teacher. See, before No Child Left Behind was implemented, there was already a growing call for some standardization or assessment to merit a high school diploma. I graduated from high school in Pennsylvania in 2001, which means I completed a “Senior Project” as my standard assessment to earn a diploma. Of course, the PSSAs (statewide standardized tests) were introduced soon thereafter, and the project-based graduation requirement went by the wayside. As a student, I neither loved nor hated the Senior Project. I complained about it with all my peers because it was new and because the previous graduating class didn’t have to do it and because none of my teachers seemed too interested. But in process, the work wasn’t bad because I picked something I liked, and I made my own plans, timeline, and goals. The only real requirements were that the project must take a minimum of 100 hours to complete (between freshman and the beginning of senior years), it must yield demonstrations of learning in three or more subject areas (I think), and it must culminate in a 15+ minute formal presentation to school shareholders (teachers, parents, administrators, and community members) with a Q&A at the end. Now, as states try to reduce the number of standardized tests students take (particularly in non-Common Core states like Virginia), “Senior Projects,” internships, and performance-based assessments are all the rage.

While many teachers, students, and researchers will argue that a shift away from the intense, nearly-constant testing of the last two decades is good overall, few seem clear on what should be next. This is usually a discussion about assessment – not learning. Most states and school divisions have no serious plans to abolish the traditional subject areas, to reduce the number of required courses in each subject, or to give students more choice or opportunities to specialize. Public schools (and their governing bodies) seem content to continue the status quo in terms of curriculum and course offerings (after all, they’re noncontroversial, safe, and easy to schedule). Instead of offering real choice, as learners might experience in college or the job market, schools are now promoting more “student voice and choice,” more station work, more targeting of learning styles, and ubiquitous differentiation within each separate subject. And that is insane. This kind of planning is time intensive and complicated, reducing a teacher’s ability to work one-on-one with students, reducing relationship-building, reducing any potential “authentic” experiences by keeping them divided by subjects, reducing the efficiency of planning and grading. Sure, a project in my English class might include content from history or math, but the students will receive no credit for it in those classes because not all my students are in the same maths or at the same levels or with the same teachers. Instead, they’ll surely be assigned yet another project or learning-style-station activity in that class, further burdening them with time-consuming projects that won’t cross over to other subjects. Enter true interdisciplinary learning. Rather than have teachers in each subject area pretend to provide choice (I’m serving up one entrée, but you can pick your sauce), why not give students a real opportunity to choose their classes? Why not give them the chance to enroll in a class that exists solely for the purpose of activating their brains through self-selected, interdisciplinary, project-based learning? More and more universities are creating interdisciplinary, project-based courses; more and more companies are looking for young employees with these experiences. These experiences lead to a wide variety of personal and academic growth, and because everything occurs in one class, it is no harder to schedule than anything else. How can we make it happen? While the final goal might be for all school work to take this form, we have to start somewhere. First, offer the interdisciplinary class; then, to make sure students actually enroll, adjust the number of required courses in each subject area, or allow the new class to substitute and earn a credit in whatever subject area the student chooses. Rather than push for more choice inside each strict, narrow subject area, we must give students real choice (while giving teachers expectations they can manage AND giving administrators courses they can facilitate). “Student voice and choice” within mandatory classes in separate, traditional subject areas is fake, phony, fraudulent. If we really care about student engagement, creativity, and higher order thinking, we need to create a class solely based upon the principles of interdisciplinary, inquiry-based problem-solving. And once we do, I want to teach it.

Extra: For additional commentary on the problems with education dogma, including learning styles, check out ClassCast Podcast Ep.016: Learning Styles < Relationships.

Pictures courtesy of JMUXLabs.org.

0 Comments

By Ryan Tibbens

Check this out: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/performance-artist-eats-120-000-banana-duct-taped-wall-calls-n1097696?cid=sm_npd_nn_tw_ma. It's funny, right? An artist, previously best known for creating a $1million solid gold toilet (recently stolen from a British palace), created a new piece called “Comedian,” which is composed of a real yellow Cavendish dessert banana duct taped to a wall. Someone paid $120,000 for it. When stories of this “art” sale hit major media outlets, those media outlets also reported the public’s “outrage.” Then, two days later, the same media outlets reported that a man claiming to be a “performance artist” ate the banana, without permission, in a performance piece he calls “Starving Artist.” Again, we were told that people were outraged. People can act outraged by the money wasted, the people who could have been helped, the degradation of art, or even the general stupidity; but reality is even more outrageous.

First, we are asked to believe this is newsworthy – some jackwagon tapes a banana to a wall; then some rich idiot pays the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree worth of tuition, room, and board for it; then some other jackwagon eats the banana. Then the art gallery curator “replaces” the banana – new banana, new tape. Their spokesperson said, “[The performance artist] did not destroy the art work. The banana is the idea.” If this is newsworthy, then we have two options: we're all idiots, OR the artists are geniuses because they are forcing us to reflect on what art is, what money is worth, what people are worth, and how to deal with idiots.

Consider the absurdity of the following screenshots from NBC and Fox News:

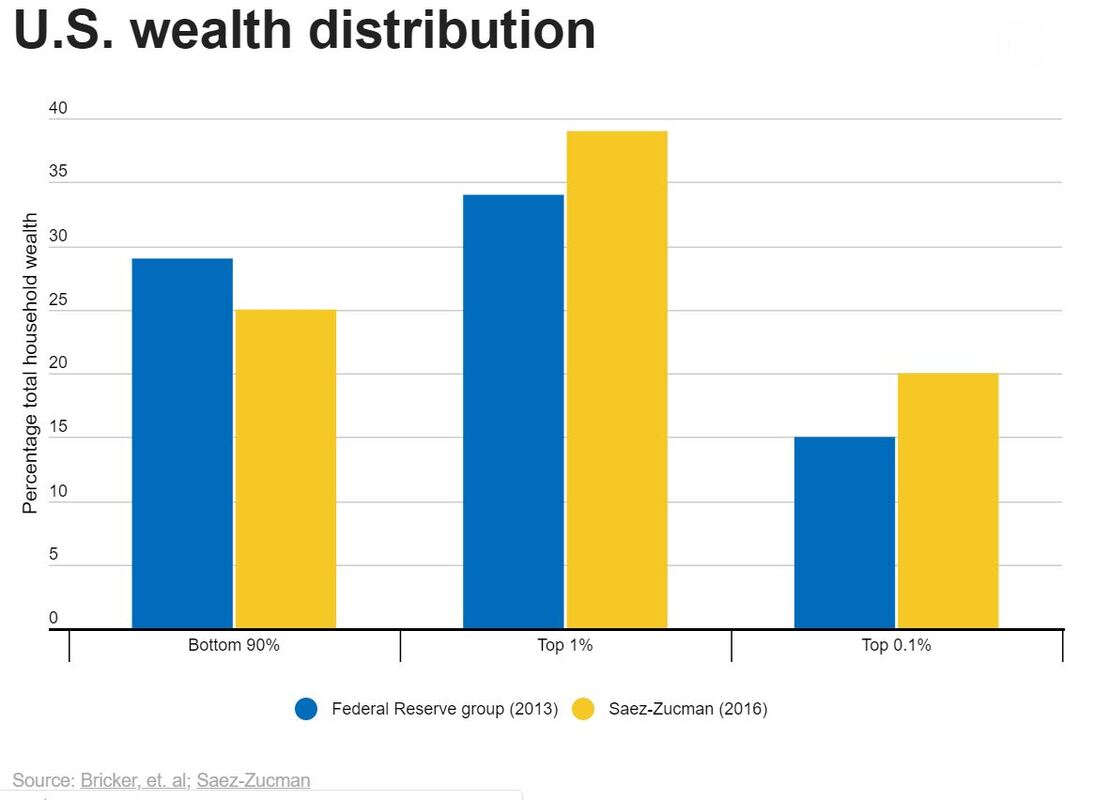

Second, in terms of wealth, the top .01% of Americans (~200,000 households) own as much wealth as the bottom 90% (~110,000,000 households). The top 10% own as much wealth as the entire middle class. I’m not a communist, but when there are nearly 500,000 unconvicted people sitting in jails, most because they can’t afford bail, and some wealthy paint-sniffer buys a banana and eight inches of tape instead of freedom for thousands of people… Well, ready the guillotine. 12.4% of US households live below the poverty line (and a whopping 48% of people in Puerto Rico). There are tens of thousands of families who earn less than $15,000 per year, and all those families know that bananas cost about 60 cents per pound – PER POUND. They also know that an entire roll of duct tape costs about five bucks. Some people don’t know what things cost because they don’t have to pay attention. The current Secretary of Education, Betsy DeVos, is massively wealthy – her family controls more than $5,400,000,000 (BILLION) dollars, nearly all of it inherited. Despite the fact that she’s never held a regular job, DeVos could buy “Comedian,” the taped banana, 45,000 times and still live like a middle class person. When the people running the country live like THIS (seriously, click the link – you will be amazed and nauseated), while the median American home is approximately 2,300 sq.ft., we have a problem, and it’s bigger than some banana art.

It seems every time I hear a debate over refugees and asylum, somebody says, "It's not that I'm opposed to helping, but we can't even afford to take care of our own." But that's not true. We can take care of our own. We can take care of every person in the country if we want, and substantially more than that too. We choose not to. I guess what I’m trying to say is that this artwork isn’t the real story – wealth inequality is. You don't have to be a communist to agree that something is wrong, and you don't have to be a communist to see that massive wealth inequality is bad morally and economically. If you’re outraged by the banana art shenanigans but don’t connect the absurdity to excessive wealth, then your outrage is misplaced. The banana art is just a symptom of the problem. And who knows? Maybe the artist was trying to make this point all along. For now, eat your bananas, and eat the rich.

By Ryan Tibbens

(Order information available at the bottom.)

The novel, which follows a white tweenager and black man as they run away from abuse and oppression down the Mississippi River, is not only anti-slavery, but anti-racist as well, an uncommon position in the 1880s. Many modern Americans fail to realize that even most abolitionists held intensely racist beliefs. However, Mark Twain was not among them. After being asked about black students entering prestigious universities in 1885, Twain had this to say: "I do not believe I would very cheerfully help a white student who would ask a benevolence of a stranger, but I do not feel so about the other color. We have ground the manhood out of them, & the shame is ours, not theirs; & we should pay for it." Twain went on to pay the full tuition and costs at Yale Law School for Warner T. McGuinn, one of the first black students at the school and later a lawyer praised by Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and others. The point here is that the novel is not a promotion of slavery or racism; instead, it is biting satire of all the worst parts of American culture (in Twain's eyes) -- racism, slavery, abusive parents, alcoholism, blind nationalism, religious revival movements, bawdy entertainment, con men, and stupid, ignorant, gullible, and mean people of all kinds. Unfortunately, people have always misunderstood the book. After its initial publication, it was criticized as "indecent" and "shameful" because of its humor, its use of a child narrator, its use of dialect, and even its anti-racist message. By the second half of the 20th century, people began to object to the book's inclusion of the dreaded "n-word." However, even that criticism was not always genuine or fair. Many people who objected to the book's message of racial equality and inclusion used the racial slur as an excuse to remove the novel from schools. More recently, people offer sincere objections to the book's racial slurs. One professor, Dr. Alan Gribben, recently revised and republished The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn through a company called NewSouth Publishing; in his text, he replaces every instance of the word "nigger" with the word "slave." Gribben claims to have made the change to reduce teachers' and students' discomfort with the text and class discussions; however, it renders the book colorblind. Gribben's edits put modern readers' focus on slavery, which had been illegal for nearly two decades when Twain published the novel, rather than race, which is the real core of the book. Consider that Twain writes and publishes this book in 1884 but sets it in the 1830s or 1840s. Why? Because a story with a race-related moral would be better understood by his audience if put in the context of slavery. When we replace racial terms with slavery terms, we confuse the issues. We forget that the vast majority of slaves in world history have not been black and that the vast majority of black people who have ever lived have not been slaves. Surely Twain opposed slavery, but the slavery issue was mostly settled at the time of publication. This is a book about (and against) racism. People's objections to Twain's use of the n-word are fine on the surface, except that the book is among the most anti-racist books of its era, perhaps any era; the language is more symptomatic of time period and realism than intent. That is not to say that readers' concerns, objections, and feelings aren't legitimate -- they are. Revered history professor Sterling Stuckey says, "In my judgment, 'Huck Finn' is one of the most devastating attacks on racism ever written.'' As intelligent, culturally-literate Americans, we must deal with a tough question -- should we ever be asked to experience discomfort on our journey to enlightenment?

Enlightenment is at the heart of this great novel. In perhaps the plot's most important moment, young Huck grapples with society's ethics, his own morals, racism, slavery, and his loyalty to his friend Jim, a runaway slave. When faced with a decision between leaving Jim to be re-enslaved far from home, returning him to his 'rightful' owner and be re-enslaved, or defying all his school, church, and social learning by working to free Jim from his new captivity and continue to help him find freedom -- a decision between doing the 'right thing' according to society or the 'right thing' according to his heart -- Huck declares, "All right then, I'll go to hell." Huck may not have achieved true enlightenment just yet, but he makes a choice that he never regrets and that shapes his future acts -- he will always do what is right, regardless of what society says. Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is a leading candidate for the title of 'Great American Novel.' It incorporates important elements of our national ethos: rugged individualism, naturalism and realism, complicated history, racism, slavery, coming of age, and -- above all -- the ongoing struggle between personal morals and social ethics. Because of the book's language, fewer and fewer teachers use this book, often deciding that "it just isn't worth the trouble anymore," but growth is rarely easy, progress requires a struggle, and art thrives on challenges. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, though not perfect, is special, is purposeful, is thoughtful, is moral, decent, and a must-read for any person desiring better understandings of morality, racism, or American culture. This book deserves an A+ for its literary innovations, cultural significance, and educational offerings.

Support ReadThinkWriteSpeak by using these links for purchase. You pay nothing more, but Amazon sends us a small portion of each sale to support this website and local classroom needs.

ORDER INFO: The first book link above (McDougal Littell Literary Connections) is recommended because it the copy that Mr. Tibbens has and that the school offers. Class discussions and lectures will include book references and page numbers from that edition; it is available for purchase via the link AND for free borrowing from the school book room. The Bantam (2nd above) and Dover (3rd above) editions are of similar cost and quality, though the Bantam version has slightly larger margins for annotating. The Norton (4th above) is a nicer binding and includes analytical and informative support texts, but it does cost a bit more. The 5th book is a reprinting of the original text, including illustrations and other extras from early printings. Any original, unabridged edition of the book is acceptable for class use. Ebooks and audiobooks are widely available (often for free/cheap), but they make annotations extremely difficult, so they are not recommended unless paired with a traditional hard copy. Contact the teacher with questions.

Just for fun...

Introduction and Review by Ryan Tibbens

(Order information available at the bottom of the review.)

Simply put, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is one of the most important books written in American history. Widely regarded as the best American slave narrative, it was written by Frederick Douglass at the age of 27, just a few years after gaining his freedom. Like most slave narratives, it includes testimonials and introductions by prominent white abolitionists to lend ethos to the author, but upon reading, modern audiences can scarcely imagine that Douglass needed a boost in credibility. His narrative structure is sound, imagery is vivid, diction is impeccable. His appeals to human decency and justice are cries we can't unhear. An early review in William Lloyd Garrison's newspaper proclaimed, “It will leave a mark upon this age which the busy finger of time will deepen at every touch. It will generate a public sentiment in this nation, in the presence of which our pro-slavery laws and constitutions shall be like chaff in the presence of fire. It contains the spark which will kindle up the smouldering [sic] embers of freedom in a million souls, and light up our whole continent with the flames of liberty."

Frequently cited as an inspiration by civil rights champions and politicians, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass also functions well in modern English and social studies classrooms. Its historical significance and status as a trusted primary source are impressive, but Douglass's style and advanced, sometimes intimidating, vocabulary provide students opportunities to study rhetoric, syntax, diction, style, and more. Douglass's writings have been cited on the Advanced Placement English Language & Composition exam no fewer than three times and offer an opportunity to become more comfortable with older non-fiction, which is traditionally the most challenging multiple choice reading passage on that exam.

For use in my AP English Language & Composition classes, students focus on (and annotate) the author's rhetoric and style, and they give special attention to content related to education and personal freedom. Douglass's exquisite writing makes the first task easy; his candor eases the second as well. In Chapter VI, Douglass writes that his master once said if he was taught to read, "'there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.' These words sank deep into my heart, stirred up sentiments within that lay slumbering, and called into existence an entirely new train of thought. It was a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things, with which my youthful understanding had struggled, but struggled in vain. I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty—to wit, the white man's power to enslave the black man. It was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom. It was just what I wanted, and I got it at a time when I the least expected it. Whilst I was saddened by the thought of losing the aid of my kind mistress, I was gladdened by the invaluable instruction which, by the merest accident, I had gained from my master. Though conscious of the difficulty of learning without a teacher, I set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read. The very decided manner with which he spoke, and strove to impress his wife with the evil consequences of giving me instruction, served to convince me that he was deeply sensible of the truths he was uttering. It gave me the best assurance that I might rely with the utmost confidence on the results which, he said, would flow from teaching me to read. What he most dreaded, that I most desired. What he most loved, that I most hated. That which to him was a great evil, to be carefully shunned, was to me a great good, to be diligently sought; and the argument which he so warmly urged, against my learning to read, only served to inspire me with a desire and determination to learn. In learning to read, I owe almost as much to the bitter opposition of my master, as to the kindly aid of my mistress. I acknowledge the benefit of both."

The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is fully deserving of a 5/5 rating. And weighing in at less than 100 pages, even the busiest student can make time to read and annotate it well in just a couple weeks.

For book order purposes, I recommend the Dover Thrift edition because it is accurate, complete, and cheap. The print and margins are somewhat small, so annotations can sometimes be tricky for students who write too much or have large handwriting, but the monetary trade-off usually makes it worthwhile. The other $5-7 versions available on Amazon.com are of varying quality, many having printing errors, binding problems, small margins, or missing prefaces/introductions. Therefore, I personally recommend the cheaper Dover Thrift (which I use) or the Penguin Classic edition, which includes other Douglass writings and speeches. The full text is widely available online, free of charge, but few students have ever submitted quality annotations in an Ebook or from a .pdf. Proceed with caution. Still, it is an option. The book is also available at most major book stores. If you have questions about obtaining a copy, let us know. Related Readings/Materials

ReadThinkWriteSpeak and the ClassCast Podcast are Amazon affiliates. As such, they receive a small portion of any purchases made after clicking links on this page. All proceeds are reinvested into this website, the podcast, or classroom/school supplies for the author/s and students.

|

Read.Think.Write.Speak.Because no one else Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed