|

Alexander Pope once wrote that "To err is human; to forgive, divine."

John Dewey later remarked that "Failure is instructive. The person who really thinks learns quite as much from his failures as from his successes." We've spent much of our year in AP Lang learning about close reading, critical thinking, analytical and persuasive writing, and how to speak respectfully yet critically of justice, morals, bias, racism, and more. Now, it is time for us to learn about our errors, our mistakes -- how and why we make them, how to be aware of their existence, and how to learn from them. Each of the books listed below represents a "synthesis" essay (book) about human mistakes and how we think. They are also common reading assignments in entry-level college communications, rhetoric, and culture classes (and came highly recommended by a few of Mr. Tibbens' former students now studying at prestigious universities across the country).

ASSIGNMENT:

Students should look up each book. Read some reviews. Ask around. Rank book choices from most-to-least desirable. Do not purchase, borrow, or otherwise obtain a book until after in-class sign-ups and group assignments. Mr. Tibbens will do his best to honor students' book requests/priorities, but some adjustments may be required in order to have functional, balanced groups. ~Sign up the book you actually want to read, not just one that your friends are also choosing.~ Once the assignment "goes live," students must obtain copies of their books, read critically, and annotate for three concepts/features: 1) Use/synthesis of evidence, 2) Tone shifts, and 3) Insights about being wrong (content). If you have questions about the books or the associated assignments, contact Mr. Tibbens via email.

Disclosure: Students may obtain books via the Amazon.com links below, other book sellers, the school or public libraries, or other sources. Students are encouraged to use a print copy of the book, rather than an ebook/audiobook, for annotation purposes. The English dept. does not own copies of these books to lend, as has been the case for most previous assignments; if this presents a hardship for your family, contact Mr. Tibbens via email as soon as possible. Purchases made via the Amazon.com links below cost you no additional money, but a small percentage of each purpose go back to supporting this website and additional materials/supplies for classroom use. Contact Mr. Tibbens if you have any questions or concerns regarding the books, links, etc.

Book #1: The Coddling of the American Mind

Book #2: Being Wrong

Book #3: Talking to Strangers

Book #4: Thinking in Bets

0 Comments

By Ryan Tibbens

Check this out: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/performance-artist-eats-120-000-banana-duct-taped-wall-calls-n1097696?cid=sm_npd_nn_tw_ma. It's funny, right? An artist, previously best known for creating a $1million solid gold toilet (recently stolen from a British palace), created a new piece called “Comedian,” which is composed of a real yellow Cavendish dessert banana duct taped to a wall. Someone paid $120,000 for it. When stories of this “art” sale hit major media outlets, those media outlets also reported the public’s “outrage.” Then, two days later, the same media outlets reported that a man claiming to be a “performance artist” ate the banana, without permission, in a performance piece he calls “Starving Artist.” Again, we were told that people were outraged. People can act outraged by the money wasted, the people who could have been helped, the degradation of art, or even the general stupidity; but reality is even more outrageous.

First, we are asked to believe this is newsworthy – some jackwagon tapes a banana to a wall; then some rich idiot pays the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree worth of tuition, room, and board for it; then some other jackwagon eats the banana. Then the art gallery curator “replaces” the banana – new banana, new tape. Their spokesperson said, “[The performance artist] did not destroy the art work. The banana is the idea.” If this is newsworthy, then we have two options: we're all idiots, OR the artists are geniuses because they are forcing us to reflect on what art is, what money is worth, what people are worth, and how to deal with idiots.

Consider the absurdity of the following screenshots from NBC and Fox News:

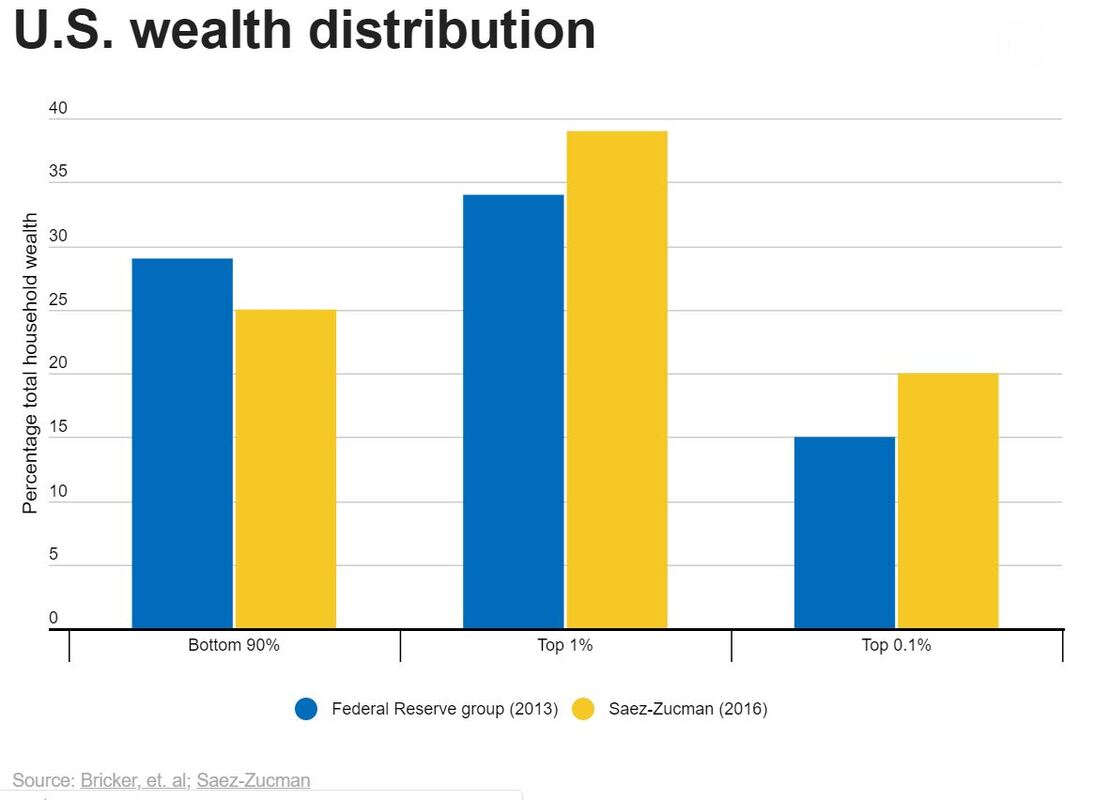

Second, in terms of wealth, the top .01% of Americans (~200,000 households) own as much wealth as the bottom 90% (~110,000,000 households). The top 10% own as much wealth as the entire middle class. I’m not a communist, but when there are nearly 500,000 unconvicted people sitting in jails, most because they can’t afford bail, and some wealthy paint-sniffer buys a banana and eight inches of tape instead of freedom for thousands of people… Well, ready the guillotine. 12.4% of US households live below the poverty line (and a whopping 48% of people in Puerto Rico). There are tens of thousands of families who earn less than $15,000 per year, and all those families know that bananas cost about 60 cents per pound – PER POUND. They also know that an entire roll of duct tape costs about five bucks. Some people don’t know what things cost because they don’t have to pay attention. The current Secretary of Education, Betsy DeVos, is massively wealthy – her family controls more than $5,400,000,000 (BILLION) dollars, nearly all of it inherited. Despite the fact that she’s never held a regular job, DeVos could buy “Comedian,” the taped banana, 45,000 times and still live like a middle class person. When the people running the country live like THIS (seriously, click the link – you will be amazed and nauseated), while the median American home is approximately 2,300 sq.ft., we have a problem, and it’s bigger than some banana art.

It seems every time I hear a debate over refugees and asylum, somebody says, "It's not that I'm opposed to helping, but we can't even afford to take care of our own." But that's not true. We can take care of our own. We can take care of every person in the country if we want, and substantially more than that too. We choose not to. I guess what I’m trying to say is that this artwork isn’t the real story – wealth inequality is. You don't have to be a communist to agree that something is wrong, and you don't have to be a communist to see that massive wealth inequality is bad morally and economically. If you’re outraged by the banana art shenanigans but don’t connect the absurdity to excessive wealth, then your outrage is misplaced. The banana art is just a symptom of the problem. And who knows? Maybe the artist was trying to make this point all along. For now, eat your bananas, and eat the rich.

Introduction and Review by Ryan Tibbens

ORDER HERE: Justice: What Is the Right Thing to Do?

Michael J. Sandel's Justice: What Is the Right Thing to Do? is both a book and a college course. In fact, Sandel's class is the most popular course ever offered at Harvard University. You can watch large portions of the class free of charge at JusticeHarvard.org and on YouTube. A few years ago, a student told me about the class and its videos; she said that parts of his lectures and discussions reminded her of my class and that I might enjoy it. I did. I watched all 15+ hours of video and immediately began thinking about how to implement it in class. Of course, I couldn't show that much video, particularly in a high school English class, so when I found out that Sandel had written a book based upon the course, I was thrilled.

An introduction to moral and political philosophy, Justice: What Is the Right Thing to Do? now acts as a cornerstone in my AP English Language and Composition classes because it forces deep thinking, critical questioning, and rhetorical discussions. Without my prompting, students will reference the book all year long in a variety of discussions and essays; they will use it to question their classmates and support arguments in their own essays. Interestingly, several universities now use questions drawn from this book for supplemental admissions essays, in admissions interviews, and in scholarship interviews (including the University of Virginia's Jefferson Scholars program). Any person interested in moral or political philosophy, or interested in better understanding what they think is right and (more importantly) WHY they think that, should consider this a must read. It earns 5/5 stars and a prominent place in my course syllabus. ORDER HERE: Justice: What Is the Right Thing to Do?

Other books by Michael J. Sandel...

Compiled by Ryan Tibbens for educational purposes only

On this Juneteenth, 2019, the United States House of Representatives held hearings on reparations for slavery. This is not a new idea, but new voices made themselves heard and breathed life into an otherwise stale debate. This article serves as a brief, basic introduction to the new debate; it includes two video clips from today's congressional testimonies, an excerpt from a best-selling modern philosophy book, and a video of the book's author teaching class. Additionally, this article includes a new feature: reader surveys. There is one survey in the beginning; use it to indicate your beliefs now. The other survey is at the end of the article; use it to indicate your beliefs after considering the compiles sources.

Before launching into the sources, remember this: you can't reasonably claim pride in your community's past achievements if you won't also accept shame for the past failures. Source #1) An argument in favor of reparations by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Source #2) An argument against reparations by Coleman Hughes. Source #3a) An excerpt from Michael J. Sandel's Justice, in which he discusses loyalty, community, and individuality. (Full text available here.) ~~ WHAT DO WE OWE ONE ANOTHER? / DILEMMAS OF LOYALTY ~~ It’s never easy to say, “I’m sorry.” But saying so in public, on behalf of one’s nation, can be especially difficult. Recent decades have brought a spate of anguished arguments over public apologies for historic injustices. -- Apologies and Reparations -- Much of the fraught politics of apology involves historic wrongs committed during World War II. Germany has paid the equivalent of billions of dollars in reparations for the Holocaust, in the form of payments to individual survivors and to the state of Israel. Over the years, German political leaders have offered statements of apology, accepting responsibility for the Nazi past in varying degrees. In a speech to the Bundestag in 1951 , German chancellor Konrad Adenauer claimed that “the overwhelming majority of the German people abominated the crimes committed against the Jews and did not participate in them.” But he acknowledged that “unspeakable crimes have been committed in the name of the German people, calling for moral and material indemnity.” In 2000, German president Johannes Rau apologized for the Holocaust in a speech to the Israeli Knesset, asking “forgiveness for what Germans have done.” Japan has been more reluctant to apologize for its wartime atrocities. During the 1930s and ’40s, tens of thousands of Korean and other Asian women and girls were forced into brothels and abused as sex slaves by Japanese soldiers. Since the 1990s, Japan has faced growing international pressure for a formal apology and restitution to the so-called “comfort women.” In the 1990s, a private fund offered payments to the victims, and Japanese leaders made limited apologies. But as recently as 2007, Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe insisted that the Japanese military was not responsible for coercing the women into sexual slavery. The U.S. Congress responded by passing a resolution urging the Japanese government to formally acknowledge and apologize for its military’s role in enslaving the comfort women. Other apology controversies involve historic injustices to indigenous peoples. In Australia, debate has raged in recent years over the government’s obligation to the aboriginal people. From the 1910s to the early 1970s, aboriginal children of mixed race were forcibly separated from their mothers and placed in white foster homes or settlement camps. (In most of these cases, the mothers were aborigines and the fathers white.) The policy sought to assimilate the children to white society and speed the disappearance of aboriginal culture. The government-sanctioned kidnappings are portrayed in Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002), a movie that tells the story of three young girls who, in 1931, escape from a settlement camp and set out on a 1 ,200-mile journey to return to their mothers. In 1997, an Australian human rights commission documented the cruelties inflicted on the “stolen generation” of aborigines, and recommended an annual day of national apology. John Howard, the prime minister at the time, opposed an official apology. The apology question became a contentious issue in Australian politics. In 2008, newly elected prime minister Kevin Rudd issued an official apology to the aboriginal people. Although he did not offer individual compensation, he promised measures to overcome the social and economic disadvantages suffered by Australia’s indigenous population. In the United States, debates over public apologies and reparations have also gained prominence in recent decades. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law an official apology to Japanese Americans for their confinement in internment camps on the West Coast during World War II. In addition to an apology, the legislation provided compensation of $20,000 to each survivor of the camps, and funds to promote Japanese American culture and history. In 1993, Congress apologized for a more distant historic wrong — the overthrow, a century earlier, of the independent kingdom of Hawaii. Perhaps the biggest looming apology question in the United States involves the legacy of slavery. The Civil War promise of “forty acres and a mule” for freed slaves never came to be. In the 1990s, the movement for black reparations gained new attention. Every year since 1989, Congressman John Conyers has proposed legislation to create a commission to study reparations for African Americans. although the reparations idea has won support from many African American organizations and civil rights groups, it has not caught on with the general public. Polls show that while a majority of African Americans favor reparations, only 4 percent of whites do. Although the reparations movement may have stalled, recent years have brought a wave of official apologies. In 2007, Virginia, which had been the largest slaveholding state, became the first to apologize for slavery. A number of other states, including Alabama, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, and Florida, followed. And in 2008, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution apologizing to African Americans for slavery and for the Jim Crow era of racial segregation that extended into the mid-twentieth century. Should nations apologize for historic wrongs? To answer this question, we need to think through some hard questions about collective responsibility and the claims of community. The main justifications for public apologies are to honor the memory of those who have suffered injustice at the hands (or in the name) of the political community, to recognize the persisting effects of injustice on victims and their descendants, and to atone for the wrongs committed by those who inflicted the injustice or failed to prevent it. As public gestures, official apologies can help bind up the wounds of the past and provide a basis for moral and political reconciliation. Reparations and other forms of financial restitution can be justified on similar grounds, as tangible expressions of apology and atonement. They can also help alleviate the effects of the injustice on the victims or their heirs. Whether these considerations are strong enough to justify an apology depends on the circumstances. In some cases, attempts to bring about public apologies or reparations may do more harm than good by inflaming old animosities, hardening historic enmities, entrenching a sense of victimhood, or generating resentment. Opponents of public apologies often voice worries such as these. Whether, all things considered, an act of apology or restitution is more likely to heal or damage a political community is a complex matter of political judgment. The answer will vary from case to case. -- Should We Atone for the Sins of our Predecessors? -- But I would like to focus on another argument often raised by opponents of apologies for historic injustices — a principled argument that does not depend on the contingencies of the situation. This is the argument that people in the present generation should not — in fact, cannot — apologize for wrongs committed by previous generations. To apologize for an injustice is, after all, to take some responsibility for it. You can’t apologize for something you didn’t do. So, how can you apologize for something that was done before you were born? John Howard, the Australian prime minister, gave this reason for rejecting an official apology to the aborigines: “I do not believe that the current generation of Australians should formally apologize and accept responsibility for the deeds of an earlier generation.” A similar argument was made in the U.S. debate over reparations for slavery. Henry Hyde, a Republican congressman, criticized the idea of reparations on these grounds: “I never owned a slave. I never oppressed anybody. I don’t know that I should have to pay for someone who did [own slaves] generations before I was born.” Walter E. Williams, an African American economist who opposes reparations, voiced a similar view: “If the government got the money from the tooth fairy or Santa Claus, that’d be great. But the government has to take the money from citizens, and there are no citizens alive today who were responsible for slavery.” Taxing today’s citizens to pay reparations for a past wrong may seem to raise a special problem. But the same issue arises in debates over apologies that involve no financial compensation. With apologies, it’s the thought that counts. The thought at stake is the acknowledgment of responsibility. Anyone can deplore an injustice. But only someone who is somehow implicated in the injustice can apologize for it. Critics of apologies correctly grasp the moral stakes. And they reject the idea that the current generation can be morally responsible for the sins of their forebears. When the New Jersey state legislature debated the apology question in 2008, a Republican assemblyman asked, “Who living today is guilty of slaveholding and thus capable of apologizing for the offense?” The obvious answer, he thought, was no one: “Today’s residents of New Jersey, even those who can trace their ancestry back to . . . slaveholders, bear no collective guilt or responsibility for unjust events in which they personally played no role.” As the U.S. House of Representatives prepared to vote an apology for slavery and segregation, a Republican critic of the measure compared it to apologizing for deeds carried out by your “great-great-great-grandfather.” -- Moral Individualism -- The principled objection to official apologies is not easy to dismiss. It rests on the notion that we are responsible only for what we ourselves do, not for the actions of other people, or for events beyond our control. We are not answerable for the sins of our parents or our grandparents or, for that matter, our compatriots. But this puts the matter negatively. The principled objection to official apologies carries weight because it draws on a powerful and attractive moral idea. We might call it the idea of “moral individualism.” The doctrine of moral individualism does not assume that people are selfish. It is rather a claim about what it means to be free. For the moral individualist, to be free is to be subject only to obligations I voluntarily incur; whatever I owe others, I owe by virtue of some act of consent — a choice or a promise or an agreement I have made, be it tacit or explicit. The notion that my responsibilities are limited to the ones I take upon myself is a liberating one. It assumes that we are, as moral agents, free and independent selves, unbound by prior moral ties, capable of choosing our ends for ourselves. Not custom or tradition or inherited status, but the free choice of each individual is the source of the only moral obligations that constrain us. You can see how this vision of freedom leaves little room for collective responsibility, or for a duty to bear the moral burden of historic injustices perpetrated by our predecessors. If I promised my grandfather to pay his debts or apologize for his sins, that would be one thing. My duty to carry out the recompense would be an obligation founded on consent, not an obligation arising from a collective identity extending across generations. Absent some such promise, the moral individualist can make no sense of a responsibility to atone for the sins of my predecessors. The sins, after all, were theirs, not mine. If the moral individualist vision of freedom is right, then the critics of official apologies have a point; we bear no moral burden for the wrongs of our predecessors. But far more than apologies and collective responsibility are at stake. The individualist view of freedom figures in many of the theories of justice most familiar in contemporary politics. If that conception of freedom is flawed, as I believe it is, then we need to rethink some of the fundamental features of our public life. As we have seen, the notions of consent and free choice loom large, not only in contemporary politics, but also in modern theories of justice. Let’s look back and see how various notions of choice and consent have come to inform our present-day assumptions. An early version of the choosing self comes to us from John Locke. He argued that legitimate government must be based on consent. Why? Because we are free and independent beings, not subject to paternal authority or the divine right of kings. Since we are “by nature, all free, equal and independent, no one can be put out of this estate, and subjected to the political power of another, without his own consent.” [Sandel continues by making connections to the philosophies of Immanuel Kant and John Rawls.] Source 3b) A recording of Michael Sandel teaching his "Justice" course at Harvard, this segment addresses many of the topics and texts mentioned above in 'Source 3a.' This is the most popular course in the history of Harvard University and is fully available online for free at JusticeHarvard.org as well as his Harvard webpage and YouTube. Both the book Justice and the class are strongly recommended.

By Ryan Tibbens

Kyle Kashuv is everywhere this week. Everywhere except Harvard, that is.

You see, Kashuv survived the Parkland school shooting and went on to become a conservative activist and rising star in Turning Point USA, a conservative political group (believed by many to be a white nationalist organization). His was a singular but confident voice that did not blame the NRA nor call for greater gun control after the shooting. He earned excellent grades (weighted GPA of 5.345, unweighted GPA of 3.9), graduated second in his class, and scored 1550 on his SAT and was admitted into Harvard University. And then, in May 2020, a former friend revealed racist, derogatory, and generally dim-witted comments and messages written by Kashuv in private message groups. It turns out that, in addition to being an excellent student and conservative political activist, Kashuv is (was?) a racist and a douche bag. When that information went public, Harvard re-evaluated his acceptance and revoked it. After a series of letters, emails, and messages back and forth, the school indicated that the decision was final. Predictably, a media frenzy ensued. Many people applauded the decision; after all, there should be no place for that kind of racism in modern America. Many others condemned the decision; of course, everyone makes mistakes, and people can learn and improve and apologize. And apologize he did. Nearly every media outlet in the country offered its take on the situation: The Atlantic, NPR, Breitbart, Vox, even Education Week in addition to the Times, Post, Tribune, and the rest. Here we are now. Everyone sees this as a matter of progress, of just deserts, of political correctness, or of censorship. The debate is all about should and shouldn't, good and bad, right and wrong, left and right, new and old. But maybe the real debate should be Harvard itself, not just Kashuv's college plans. Harvard is a private institution (despite massive government subsidies), so it has more freedom in establishing admissions criteria than do most public schools. To all the conservatives who think this is horrible, terrible, the end of free speech, etc. -- how is this different than the Colorado baker who refused to make a wedding cake for a gay couple? Those who championed the free market and the private business's right to choose should be applauding Harvard. Then again, those who decried the baker for not serving everyone equally might need to reassess their views on Kashuv's rejection. Kashuv committed no crime, engaged in no violence; in fact, his stupidity was generally limited to private conversations in which friends were trying to be outrageous, meaning no one would ever have known if someone didn't leak the info. We can argue all day about the friend's motives or moral imperatives or whatever, but that, like Kashuv himself, isn't the source of the current conflict. The problem is Harvard. Once a small, Puritan school, Harvard is one of the wealthiest and most powerful educational institutions on the planet. It is the oldest college in the United States and issues one of the most desirable degrees anywhere. Harvard influences every major industry, every branch of government. Though it shed its Puritan ties long ago, Harvard seems determined to enforce some nebulous modern morality. The school recently fired Ronald Sullivan, "the first black faculty dean to preside over a dorm at Harvard" and a world-class defense attorney, because of his role as attorney to disgraced movie producer Harvey Weinstein. Yet Harvard once held slaves, supported Apartheid in South Africa, excluded female students, and engaged in a wide variety of questionable investment, admissions, and research practices. Just recently, the school was sued for using racial quotas to limit Asian-American admissions; this was not the first time the school had used demographics to sway admissions. In the 1970s, students began "divestment" movements to force the university to cut financial ties with oppressors, abusers, and political ne'er-do-wells: apartheid, tobacco companies, Sudanese genocide, fossil fuels, and more. The Harvard Management Company repeatedly refused to divest, stating that "operating expenses must not be subject to financially unrealistic strictures or carping by the unsophisticated or by special interest groups." Does the university stand by that language today? Are finances steering their decisions in these intensely public debates? But now Harvard has revoked an admission offer because a student used racial slurs and offensive language in private messages when he was 16. Kashuv survived the Parkland shooting and claims that the event forced him to reassess his values and goals; he claims to be an entirely different person than the teen who made the terrible, racist jokes two years previously; he has admitted to his mistakes and apologized. What is Harvard saying by revoking the admission offer? Is Harvard suddenly affected by some higher morality? Is use of the 'n-word' literally unforgivable? Is the rejection politically motivated? While the motives, aside from some vague morality, are unclear, one thing is certain -- this is not about academics. David Hogg, another survivor of the Parkland shooting, will be attending Harvard next fall despite his 1270 SAT score (the bottom 25% of those admitted had an average SAT score of 1460 out of 1600; Kashuv scored 1550). If one of the most academically selective institutions in the world is allowing academics take a backseat to personal behaviors or ideologies in the admissions process, then Harvard has created its own new problem. Cancel Culture has reached the most elite institutions, and now we, as Americans, need to figure out how to proceed -- Can people be forgiven? Can (or should) we tolerate non-violent bigotry? (See this related article from Read.Think.Write.Speak.) Here's the solution. It's easy. Harvard should publish its guidelines for morality the same way they release average GPAs and SAT scores. As a private institution, Harvard has the right to decline any student who doesn't fit their criteria and mission, but to help applicants and avoid future problems like this, the university should state clearly what is or is not acceptable behavior. Directly and indirectly, Harvard influences much of American life, and if the school seeks to affect our national morality, maybe they could do everyone a favor and just say what they believe (and what they think everyone else should believe too).

"Achieve an Informed and Common Sense Opinion on the United States' Dealings in the Middle East: An Anthology" -- Compiled by Ryan Tibbens for educational purposes ONLY

On this Flag Day, we should all consider what our flag stands for, not just here in the United States, but around the world too. We should better understand how actions taken under that flag and paid for by American citizens affect peace, prosperity, and geopolitics around the world. This 'article' is more of an anthology, a compilation of reliable sources and literary connections, designed to inform discussions of American involvement in the Middle East.

Before you ever suggest raising taxes for public services or cutting social safety nets to save money, you should better understand how our federal government effectively gives away our prosperity, often to countries that support our enemies. You should also try to understand why these decisions make sense to those who wield power in our government and major industries. Let's start with a trailer for a GREAT documentary. (Go watch the whole movie -- it is currently available on Amazon Prime.)

Why We Fight, a fantastic documentary (2006) by Eugene Jarecki, addresses the threat of the military-industrial-congressional complex using strong research, purposeful rhetoric, and an impressive set of interviews with ranking government and private sector leaders. Jarecki's discussion (argument?) builds on a foundation created by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in his Farewell Address.

Next, let's take a look at geopolitical dynamics in the Middle East, with extra attention paid to the two biggest players -- Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Vox has several well-researched introductory videos on YouTube that create solid foundations for further study or (the beginnings of) informed discourse. They have also compiled a few maps (some animated) to further clarify the historical and cultural complexities of Middle Eastern politics, for example:

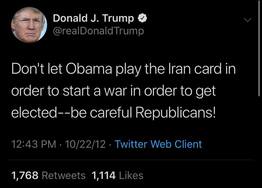

Perhaps the most urgent item in this brief compilation is the video of Senator Rand Paul speaking before the Senate on June 13, 2019 (yesterday) about the government's plans to sell arms to Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Qatar. With a determination and repetition that are both rhetorically effective and somewhat annoying by the end, Paul points out the complete lack of common sense in our approach to Middle Eastern foreign policy and arms sales. Our president and legislators seem to believe that the best path to peace in the Middle East is sending in more armaments, weapons that often end up in our enemies' hands to be used against our own young soldiers. Using the context from the previous two videos, think carefully about Senator Rand Paul's words.

Remember, we are talking about millions, billions, sometimes trillions of dollars -- and that is a lot more money than most of us can even imagine. As President Eisenhower pointed out, we could build scores of schools, hospitals, and highways with that money; we could uplift the American people. President George Washington gave similar warnings in his farewell address -- that a standing army will lead to wars and that foreign entanglements will ruin our republic. We continue to ignore good advice from two strong presidents, two of our nation's great military leaders, instead wasting tax-payers' dollars on misguided military interventions and arms sales.

How can we make sense of all this nonsense? George Orwell explained these processes clearly in his book within a book, "THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF OLIGARCHICAL COLLECTIVISM by Emmanuel Goldstein," contained in Part 2, Chapter 9 of 1984. In this section of the book, Winston, the protagonist and active opposition to the Party and Big Brother, finally gets to read from "the book." In this block of text, Orwell demonstrates his social and political clairvoyance by describing the world in which we live today.

In this writer's opinion, this is the most important source in this anthology; unfortunately, it also requires the most reading. However, if you've made it this far, it is my sincere hope that you will finish the job and read a few extra pages -- your outlook on American politics and "defense" spending will never be the same. The link above contains the full text (as well as the entire novel); you can also read here on Read.Think.Write.Speak. by clicking on the "Read More" link just below the Amazon ads. The next time a politician claims that "we can't afford" domestic programs or that "we need to raise taxes to fund public services" or that "cutting defense spending endangers all Americans as well as democracy around the world" or any such nonsense, remember what George Orwell, Rand Paul, George Washington, Dwight Eisenhower, and objective history have to say about those lies. |

Read.Think.Write.Speak.Because no one else Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed