|

By Jonathan Walthour Jonathan Walthour is a 2018 graduate of George Mason University and 2014 graduate of Heritage High School. He is a business systems analyst who enjoys spending time with friends, trading on foreign exchange markets, and has been getting more involved in the Black Lives Matter movement. Jonathan wrote this short essay and shared the videos (scroll down) to help others get a more personal, less media-centered view of the BLM protests in Washington DC. The date was June 2, 2020, and the time was around 5:00pm. A few friends and I got out of the car on Vermont Avenue and walked toward Pennsylvania Avenue, The White House. We eagerly moved toward the energized protesters. I noticed a family of five (father, mother, and four young children) with cleaning supplies trying to scrub profane anti-Trump graffiti off a nearby wall. No one said anything as we walked by, but I thought to myself: “Why bring little children to this type of atmosphere where there’s going to be a riot?” As we continued to walk, the roaring chants grow louder, and the electric atmosphere rose as well. I did not know whether to feel scared or excited; little did I know what I was about to see. As we finally turned the corner on Pennsylvania Avenue and merged into the crowd, I could not believe my eyes – Thousands upon thousands of peaceful protesters chanting the names of those brutally slain by police. There were people handing out snacks, water, sanitizer, posters, gloves, masks, eye drops – you name it; it was most likely there. The most shocking revelation was the number of demonstrators who were NOT African American marching alongside us. As a black man, it gave me hope to see people were advocating for a problem that was not necessarily “theirs” but who realized the OVERALL problem and made it theirs. By no means will anything change overnight. But day by day, more and more people become educated and aware, whether they agree to advocate for BLM (Black Lives Matter) or not. A change is going to come… in due time. We, as Americans, have the right to speak up, and we must make our voices heard. We MUST stop the brutality of law enforcement. Not all protests are riots, and not all cops are bad. But there is one common enemy: racists. We need political change and change to policing policies; cops must be held accountable when they commit a crime. The date is now June 12, and Breonna Taylor’s murderers are STILL free and getting paid…Yeah, something is not right. If you do not know the story, today’s a great day to do some reading. And if you really wish to make a difference, keep in mind it is your civic duty to vote and let your voice be heard. Reposting on social media can raise awareness and funds, but voting and expressing your own morals have even more impact.

0 Comments

"Achieve an Informed and Common Sense Opinion on the United States' Dealings in the Middle East: An Anthology" -- Compiled by Ryan Tibbens for educational purposes ONLY

On this Flag Day, we should all consider what our flag stands for, not just here in the United States, but around the world too. We should better understand how actions taken under that flag and paid for by American citizens affect peace, prosperity, and geopolitics around the world. This 'article' is more of an anthology, a compilation of reliable sources and literary connections, designed to inform discussions of American involvement in the Middle East.

Before you ever suggest raising taxes for public services or cutting social safety nets to save money, you should better understand how our federal government effectively gives away our prosperity, often to countries that support our enemies. You should also try to understand why these decisions make sense to those who wield power in our government and major industries. Let's start with a trailer for a GREAT documentary. (Go watch the whole movie -- it is currently available on Amazon Prime.)

Why We Fight, a fantastic documentary (2006) by Eugene Jarecki, addresses the threat of the military-industrial-congressional complex using strong research, purposeful rhetoric, and an impressive set of interviews with ranking government and private sector leaders. Jarecki's discussion (argument?) builds on a foundation created by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in his Farewell Address.

Next, let's take a look at geopolitical dynamics in the Middle East, with extra attention paid to the two biggest players -- Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Vox has several well-researched introductory videos on YouTube that create solid foundations for further study or (the beginnings of) informed discourse. They have also compiled a few maps (some animated) to further clarify the historical and cultural complexities of Middle Eastern politics, for example:

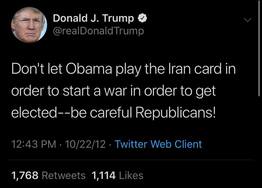

Perhaps the most urgent item in this brief compilation is the video of Senator Rand Paul speaking before the Senate on June 13, 2019 (yesterday) about the government's plans to sell arms to Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Qatar. With a determination and repetition that are both rhetorically effective and somewhat annoying by the end, Paul points out the complete lack of common sense in our approach to Middle Eastern foreign policy and arms sales. Our president and legislators seem to believe that the best path to peace in the Middle East is sending in more armaments, weapons that often end up in our enemies' hands to be used against our own young soldiers. Using the context from the previous two videos, think carefully about Senator Rand Paul's words.

Remember, we are talking about millions, billions, sometimes trillions of dollars -- and that is a lot more money than most of us can even imagine. As President Eisenhower pointed out, we could build scores of schools, hospitals, and highways with that money; we could uplift the American people. President George Washington gave similar warnings in his farewell address -- that a standing army will lead to wars and that foreign entanglements will ruin our republic. We continue to ignore good advice from two strong presidents, two of our nation's great military leaders, instead wasting tax-payers' dollars on misguided military interventions and arms sales.

How can we make sense of all this nonsense? George Orwell explained these processes clearly in his book within a book, "THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF OLIGARCHICAL COLLECTIVISM by Emmanuel Goldstein," contained in Part 2, Chapter 9 of 1984. In this section of the book, Winston, the protagonist and active opposition to the Party and Big Brother, finally gets to read from "the book." In this block of text, Orwell demonstrates his social and political clairvoyance by describing the world in which we live today.

In this writer's opinion, this is the most important source in this anthology; unfortunately, it also requires the most reading. However, if you've made it this far, it is my sincere hope that you will finish the job and read a few extra pages -- your outlook on American politics and "defense" spending will never be the same. The link above contains the full text (as well as the entire novel); you can also read here on Read.Think.Write.Speak. by clicking on the "Read More" link just below the Amazon ads. The next time a politician claims that "we can't afford" domestic programs or that "we need to raise taxes to fund public services" or that "cutting defense spending endangers all Americans as well as democracy around the world" or any such nonsense, remember what George Orwell, Rand Paul, George Washington, Dwight Eisenhower, and objective history have to say about those lies.

By Ryan Tibbens

Not a single word of the following article is intended to be critical of nor offensive to veterans, past or present, living or dead. This article is for civilian citizens who, particularly recently, have engaged in debates about war memorials, about Confederate allegiances, and about respecting our troops. I will play Devil's Advocate several times; I do not agree with every word I've written, but I strongly believe in asking the question.

It's the unofficial first day of summer, the first big barbecue of the year, when pools open and lawn furniture shakes off cobwebs. The only things more common than swarms of motorcycles are American flags and semi-heartfelt social media posts about remembering our fallen troops.

Memorial Day, a day of remembrance for those who have died while serving in the United States Armed Forces, has been celebrated, officially and otherwise, on the last Monday of May (or May 30th) since around 1868, originally commemorating those who died in the Civil War. Decoration Day was a common southern Appalachian tradition that spread across the United States after our nation's darkest years. Many Americans already observed some form of remembrance ceremony for soldiers killed in the Revolutionary War, but the Civil War truly consolidated the holiday and cemented its place in American culture. And it is worth noting that many of the biggest and most serious early celebrations took place in southern states. Have you ever argued against statues of Confederate soldiers? I have (though usually just for the fun of participating in the debate). Given the history and purpose of the holiday, I am left with a question -- if you oppose memorials for Confederate soldiers, do you also oppose Memorial Day overall? Do you at least oppose the inclusion of men killed in the Mexican-American War or World War I or Vietnam or other wars of US aggression? What is the difference? In my conversations on the subject, friends and students cite a few common reasons to remove Confederate statues: they represent racism and slavery, they represent unprovoked violence, they represent a losing effort, and they represent treason. In their own way, each of these reasons is fair and functional. However, if a person truly opposes celebrations based on those factors, then many wars -- and many, many soldiers -- should be excluded from Memorial Day. Unless you are a pure statist whose political feelings are dominated by blind patriotism, you can surely identify problems with at least some US military conflicts. The Gulf of Tonkin. The USS Maine. The Wounded Knee Massacre. The Bush family's business dealings with the Bin Ladens around the time of 9/11. The Sedition Act of 1918. War crimes and pardons. Weapons of mass destruction. We could do this for a while, but you get the point. Problems exist; mistakes were made. And if you acknowledge that mistakes have been made, repeatedly, then surely you will see that many other American soldiers are guilty of sins similar to those of the Confederates. Let's look at each of the reasons. Racism and slavery. The United States of America is a country with a long history of racism and support for slavery. The Revolutionary War yielded a racist, slave-tolerating nation. The War of 1812 did the same. The Mexican-American War attacked Hispanic Mexicans as "others" while attempting to align with and spare many White Mexicans; it also yielded new slave-holding states and territories. The Civil War was fought over slavery, but slavery was still legal in several northern states, and the Emancipation Proclamation only freed southern slaves. The Spanish-American War was supported by often-racist propaganda. The Indian wars and battles were racist to their cores. Racism has continued its influence in American geopolitics all the way through WWII in the Pacific, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and beyond. If a soldier is unworthy of honor because some part of the cause is racist, then few soldiers remain to memorialize. And what of slavery? In the South just prior to the Civil War, less than 1/3 of the white population owned slaves, and of all who did, most families owned just one slave (no less terrible, though perhaps not the image most people have thanks to Roots and 12 Years a Slave and others). Most of the wealthiest and most powerful slave owners avoided battle through military surrogates and direct legislation. Furthermore, nearly 1/3 of the Confederate army was conscripted -- drafted -- and forced to fight. Slavery was terrible, and its modern repercussions are still awful, but if 1/3 of Confederate soldiers were conscripted and 2/3 owned no slaves, then is that the best reason to avoid memorializing the dead? Unprovoked Violence. See the Mexican-American War, Spanish-American War, WWI, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War, and the Iraq War. See many, many other smaller fights along the way as well (and nearly all of US military involvement in Central and South America). If you only celebrate and remember soldiers who died in direct defense of the country, your holiday will be a short one. Losing Effort. For the pure fun of arguing, this is my favorite reason people use when protesting Confederate statues. I'm not sure I've ever encountered a Confederate-supporter who also supports 'participation trophies.' When these statues are referred to as participation trophies, reactions range from quiet scorn to full rage. Then again, the South lost, so aren't Confederate monuments really just tributes and reminders about losing? That sounds like a participation trophy. Still, as much fun as this argument is, it is flawed. How many people who oppose Confederate memorials on the grounds of 'participation trophies' would make the same argument for removing the Vietnam War Memorial or Korean War Memorial? Not many (hopefully none)... Treason. This may be the most logical reason to oppose Confederate memorials: they commemorate people who fought against the United States of America. Since the Union won, why should it tolerate celebration of those who fought against it? I don't hear much criticism of the Crazy Horse Memorial or other memorials to American Indian leaders. But that might not be entirely fair either. Is Edward Snowden and hero or traitor? Was John Brown a civil rights champion or anti-American terrorist? Was Muhammad Ali's refusal before the draft board an act of American freedom and independence or willful defiance and treason? (False dichotomies abound.) Many edgy young Americans who oppose Confederate statues claim that those men are heroes. They might also regularly speak out against the President of the United States, the legislature, the Department of Defense, and more. That kind of anti-American speech has actually been prosecutable in the past (Sedition Act of 1918 and others). Is it more important to stand with your government or with your personal obligations? If you said "personal obligations," then consider that treason is never far away. Plus, as historians so often point out, prior to the Civil War, people referred to the United States as "they" rather than "it," meaning that most citizens really saw our nation as a collection of semi-independent states, similar to the modern European Union. As such, most citizens felt a stronger allegiance to their states than their federal government, so most confederate soldiers didn't even consider their behavior truly treasonous. To be clear -- they committed treason. But so did Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, Snowden and Brown, and a few dozen more Americans who at least might be heroes despite their questionable loyalties. If it is possible to hate the sin but not the sinner, then perhaps we can hate the war but not the soldier. If we can agree that enlisted infantrymen are often used as instruments of war, then we should be able to separate degrees of guilt -- the sledge hammer is less guilty of destruction than the man swinging it. In that light, remembering and memorializing Confederate soldiers is not just acceptable, it is right. Celebrating Confederate leadership might be a different story. However, if we believe that all individual humans have the capacity to understand their circumstances, question their governments, and make their own decisions about participation in a fight, then we might be able to remove those monuments ------ but we'd need to remove a lot more than just the Confederates'.

Cognitive dissonance runs deep on Memorial Day because many Americans want to honor our troops, honor those who have sacrificed for us, but we also try not to examine their sacrifices too closely, lest we realize that their sacrifices weren't fully for "us" or that our morals conflict with the causes of some wars. Any person who can condemn Confederate memorials while defending the Vietnam War Memorial is either drowning in cognitive dissonance or knows a much more detailed, more nuanced history than I've learned.

Personally, I have no problems with Confederate monuments on battlegrounds, in museums, and at significant historical sites. Their scattering about southern capital buildings and random parks might be different, and surely the commemoration of Confederate leadership deserves more scrutiny than the simple statues that memorialize everyday Americans, the poor infantrymen that fought for their homes in the same way modern soldiers do today. If we want to have a serious and productive conversation about remembering our fallen soldiers OR about Confederate memorials, we need to more clearly identify the problems and then apply those criteria to all memorials; otherwise, cognitive dissonance wins the day. The Confederate flag, on the other hand, well, there's no way to defend that anywhere but a battlefield, and if you find someone who does, that person doesn't understand historical context or is racist or both. Food for thought...

by Ryan Tibbens

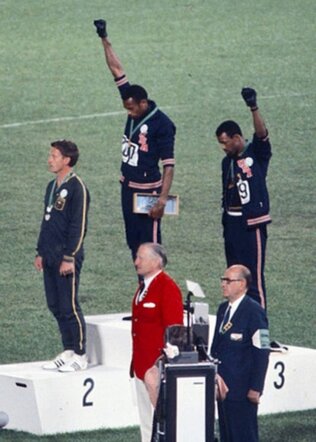

Over the last couple weeks, I've watched and listened to sports commentators, political analysts, comedians, athletes, politicians, keyboard warriors, and, well, it seems like almost everyone, argue about Colin Kaepernick and the recent national anthem protests. I've chimed in a few times, but mostly I've stayed out of it. In the last three days, I've been directly asked five times what I think. It's a little lengthy, but here's why you should be fine with the protests. I think the protests are fine. I stand for the national anthem and for the Pledge of Allegiance. I'm not offended if others don't. It's a free country. If you love the freedom of expression, it means that you love it even when it is exercised in ways you don't agree with or by people you don't like. I believe there are certain things people usually shouldn't say, but I don't suggest we legislate the language, and I don't think there should be public outrage or persecution as long as the statements are nonviolent. Sometimes I hear things I don't like, and I just let them go. This protest hurts no one, so if you disagree, the smart move is to let it go.

I recently saw a friend, a fellow teacher, post about his disagreement with and disgust for the anthem protests. He claimed that he was upset about the form of the protest, his perceived disrespect to our flag and nation and soldiers and all that, but that he was fine with players' desires for greater racial equality. I asked him what he does when students don't stand for the Pledge of Allegiance in school. I asked if their decision not to stand skewed his opinion of the students. He said he does nothing and that he is not biased against them. He said that his opinion of them is unaffected because he doesn't know their reasons. So, despite his claims, his disgust must be based, at least in part, on the protest's motives, not acts, because those same displays are tolerable from other people at other times. I suspect that most people who complain about the sitting or kneeling hold the same bias, at least subconsciously.

I've also noticed that many people complaining about the protests are hypocrites. Not everyone, but many people. Most of my friends who disagree with the protests are also those who claim to hate political correctness. They say people should toughen up and get over it; they say life isn't always fair. Political correctness is about adjusting your words and actions so as to avoid insulting or disrespecting other groups of people. But these same complainers say they feel insulted or that soldiers may feel disrespected or that veterans are hurt by these acts. If it's okay to offend some people sometimes, then it's okay to offend other people other times. You can't have it both ways. How about the fact that nearly all of my friends who support displays of the Confederate battle flag also strongly oppose Kaepernick's protest? They say they support the first amendment right to fly a flag and that they want to celebrate their heritage and that it was their ancestors' right to rebel and secede. They are defending a flag and a group of predominantly white people who took up arms against the United States of America in hopes of maintaining the institution of racial slavery. If the Confederacy's bloody resistance was just, then how is Kaepernick's quiet and peaceful protest unjust? If it is okay for someone to fly the Confederate flag, regardless of how it may make neighbors feel, then how is it so upsetting for a football player to choose to kneel during a song? These same hypocrites say they are sick of people complaining about Confederate flags, sick of people championing political correctness and limiting their freedoms. You can't have it both ways. White people complain about race riots. White people complain about civil rights parades. White people complain about traffic stoppages. Now, a low-level celebrity (catapulted to greater fame by this "controversy") is the subject of white complaint because he quietly, respectfully, and purposefully chose not to stand during the national anthem. Many people may disagree with my assertion that this protest is respectful, but consider that these football players are not interrupting the anthem: they're not shouting, cussing, spitting, rolling around, fighting, running, trampling flags. Nothing. They're just not standing. In fact, they are kneeling: a gesture that, in nearly every other setting, is considered an act of reverence. And suddenly this is an outrage. I suspect if Tim Tebow had knelt to pray during the national anthem, many white, Christian Americans would have cheered. While our country has come a long way in terms of human and civil rights for all people, we still have a long way to go. Compare poverty, education, healthcare, employment, home ownership, incarceration, average pay, or nearly any other aspect of quality of life -- you will find disparities, often large gaps, between racial groups in the United States. You will also find them between the sexes, but that's a different protest I suppose. These men are not wrong about their cause; their complaint is reasonable and worth discussing. So if the protest isn't really intrusive or abusive, and if the cause is just, how can we be upset about it? It's fine to say you would do it differently, but I don't think it makes sense to accuse them of wrongdoing. White people used to complain about black people at their dining counters or in their bus seats or in their schools. Maybe we should quit complaining when other people want to talk about inequality. |

Read.Think.Write.Speak.Because no one else Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed